|

| Riding

"One Handed" - How to ride with the reins in one hand

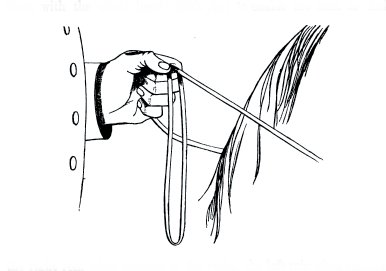

By Dan Gilmore July 6, 2012 One of the skills often ignored by modern riders in the forward system of riding is riding using only one hand on the reins. The original practical application of this particular technique is obviously military in origin with the goal of allowing a soldier to have one hand free to wield a weapon. The relevance of this technique to modern riders is the development of balance and control for the rider and lightness and self-carriage for the horse. Nolan’s technique is not to be confused with ‘neck reining’, per se, but can be used as a step to teaching a horse ‘neck reining’. This is accomplished by gradually lightening contact with the horse’s mouth and eventual lengthening of the reins (and with proper leg and seat applied in coordination with the hands). This particular issue is a subject for another article. Understanding how this technique of riding with the reins in one hand involves understanding certain not only the mechanics that are involved but certain aspects of military equitation history. Nolan makes comparisons between the Austrian and English regulation methods of using the reins in one hand, and then, through analysis of both techniques, finds the common elements (from apparently contradictory methods) of both techniques and synthesizes a more intuitive method. Most modern riders who regularly ride with the reins in one hand will probably find that they have intuitively reconstructed Nolan’s technique without any prior knowledge of Nolan’s writings. Rider’s who rarely if ever ride with reins in one hand will benefit from understanding this technique because it gives the rider the ability to apply all forms of rein with just one hand, as well as a better understanding of how rein, seat and leg work as one integrated system and not two discrete and independent elements. In this article, Lewis Edward Nolan’s “Appendix” from “The Training of Cavalry Remount Horses - A New System” (1852) will be presented with occasional notes I have added to clarify certain technical and theoretical points concerning this reining method, as well as offer insights as to how to apply this reining method to modern forward riding. Lewis Edward Nolan: How to use the Bit Reins, when held divided by the little finger of the left hand. Source: Lewis Edward Nolan; The Training of Cavalry Remount Horses - A New System; Parker, Furnivall & Parker, Military Library, Whitehall; 1852; (Appendix) “The object is through certain indications to make yourself understood and obeyed by the horse: and it is necessary that these indications shall be such, that the rider can employ them under all circumstances, and when making use of the sword.” Cavalry soldiers are ordered to turn their horses in the “ inward rein,” that is, with the right rein to the right, with the left rein to the left: but they turn them on the outward rein chiefly; this is too well know to require comment, for th invent the means of accomplishing this object with the inward rein, has long been a problem amongst the professors of horsemanship, various books having been written on the subject. General Kress v. Kressenstein, and Austrian cavalry general, proposed fastening the bit reins at a certain length, and dividing them with the whole hand, (vide fig.) To enable the man to feel the right rein when turning to the right, the left rein when turning to the left; but this and other systems proposed, have more of the disadvantage than advantage in them.  Let us select the two cavalry services, the English and Austrian, and see what the instructions are for turning a horse to either hand. In both services, the system is to turn the horse on the inward rein; to do this it is necessary to shorten that rein considerably. “To turn to the Right.” (English Cavalry Instructions.) “Turn the little finger of the left hand towards the right shoulder.” “To turn to the Right.” (Austrian Cavalry Instructions.) “Turn the little finger up towards the left shoulder.” “To turn to the Left.” (English Cavalry Instructions.) “Turn the little finger of the left hand towards the left shoulder.” “To turn to the Left.” (Austrian Cavalry Instructions.) “This is done by turning the little finger towards the right, the thumb falling forward.” Thus, the artistic contortions of the bridal hand, which turns an English horse to the right, has exactly the contrary effect upon the Austrian, for it turns him to the left; and the turn of the bridle hand, which brings the English horse to the left, makes the imperial one turn to the right. Now let anyone divide the reins with the little finger, and see whether by following these instructions, it is possible on either system to shorten the inward rein to any extent, and whether in doing so, he does not feel the other rein also; thus it cannot be with the inward rein that the horse is turned, because you cannot shorten that rein sufficiently to turn the horse without pulling the other rein at the same time. According to one of the above systems, the soldier, whilst turning to the right to meet his antagonist, is to turn his body one way and his hand another. A dragoon uses one hand for the reins, the other for the sword, and the system requires that the bridle arm shall be a fixture, that the bridle hand shall only move from the wrist, and that this latter shall be rounded outwards: the whole position is constrained, almost painful. When a troop horse is bad tempered, or tired, he is not always inclined to obey the very slight indications given “from the wrist;” thus the first time the soldier gets into difficulties he is reduced to letting the horse have his own way, or he must use his bridle hand with a little more energy (than the system admits of) to bring the horse into obedience; still he attains his object with difficulty, because the animal has not yet learnt to understand the aids which necessity has driven the rider to invent for the occasion. The horse, whilst breaking in on the snaffle, has always been turned on the inward rein, and when bitted, he is made to turn on the outside rein, without ever having been taught to do so! The conclusions to be drawn from the above are: that as both the English and Austrian Cavalry can turn their horses to the right or left, and by exactly the reverse contortions of the wrist, these said contortions can be of little consequence either way; by neither process can the inward rein be shortened without pulling the outward rein (particularly when strength is required). Thus, it is evident, it is not the inward rein which forces the horse into the new direction. The fact is, the use of the outward rein is absolutely necessary; and not only the outward rein, but I go further, and say, that “no feeling of the rein is a right one, without the assistance of the other rein and both the rider’s legs;” for in the first instance, you work on the head and neck alone, and that imperfectly, whereas, in the latter, you work upon the whole horse at once.* * Nolan is one of the few people at this time who recognized that the rein aids, leg aids and seat are integral, not discrete and independent elements of control. It also means that when you apply contact or pressure with one rein, you give with the other (and the same theory is extended to all other aids to some degree, more or less). When a horse is ridden on the snaffle, he only feels the direct pull more or less strong of the rider’s hand; with a bit [curb bit] in his mouth, the effect is different and more powerful, on the account of the lever, which tightens the curb chain on the lower jaw of the horse, and forces him to yield with the head and neck. The rider is connected with this lever by the reins, and acts upon the horse by the weight of his body, and the pressure of the legs, as much as he does with the bit. If you put a bridle in the horse’s mouth for the first time, mount him, and carry the bridle hand to the right, throwing the weight of the body to that side, the horse will turn to the right, though you may have felt the left rein more than the right one, and this because the tension of the reins which proceed from a central point being suddenly changed to a point on the right, and the horse feeling all the weight inclining to that side, as you would step under a weight your were carrying, to prevent it from falling, so does the horse feel the necessity of following, till the equilibrium between himself and his load be re-established. How useless then are all those studied and difficult movements of the bridle hand, since, turn you little finger into whatever difficult position you like, if you bring at the same time your bridle hand and body to the same side, to that side will the horse turn. Let us therefore profit by this natural inclination of the horse, and impress those aids upon him by education, which by instinct he is already inclined to obey.* * It is worth noting at this point that Nolan uses the term “Snaffle” in the modern conventional sense of the word. However, he uses the term ‘bit’ to denote ‘curb bit’. Nolan is specifically talking about the use of a double bridle but the same method of reining applies if one is using just a snaffle or just a curb bit. This reining method is also well suited for use with hackamores, particularly the ‘mechanical’ types. The life of the cavalry soldier must often depend upon his being able to turn his horse to either hand: it is therefore important that means should be placed at the man’s disposal to enable him to attain his object, with some degree of certainty; the system should be one which can be carried out by all men upon all horses; and the aids should be natural and easy to the man, and intelligible to the animal; to this purpose I think that The position and action of the bridle hand and arm should be as follows: The upper arm perpendicular from the shoulder, the lower arm resting lightly on the hip for support.* * This does not mean to fix your elbow and lower arm in one position. The rider must follow the horse’s mouth with the hand to maintain even contact and support if needed. With the modern Forward Seat, I recommend you use an arm position normal to the Forward Seat rather than the position used for the old Military Seat. Bridle hand opposite the centre, and about three inches from the body, with the knuckles towards the horse’s head, thumb pointing across the body, and a little to the right of front, the hand as low as the saddle will allow of, held naturally without constraint.* * Having one’s hand this close to one’s body isn’t compatible with the modern Forward Seat, where a much shorter rein is required. Again, with a Forward Seat, set the length of your reins for what is comfortable and effective for that seat to prevent yourself from ‘throwing away’ any leverage you may need in an emergency situation. The wrist in a natural position, not rounded outwards, which deprives the hand of the action from front to rear, and makes the whole arm stiff. The bit [curb] reins divided by the little finger, the snaffle reins brought through the full of the hand, the thumb upon the reins, but not pressed down upon them, to avoid giving stiffness to he hand.* * This is a slightly different ‘hold’ of the double bridle reins than the more standard ‘French Hold’ used by some modern riders (and, for that matter, US Cavalry riders up until the demise of horse cavalry). In dividing the bit reins with the little finger, the right rein which passes over the finger is always a little longer than the other and requires to be shortened; if this is not attended to, the horse is ridden chiefly on the left rein, he is wrongly “placed” from the beginning, (his head being bent to the left,) and he can never work well; for one of the great principles of Equitation is, when moving in a straight line to keep your horse’s head straight, and when turning to either hand, to let the horse look the way his is going. “To Turn to the Right.” Carry your hand to the right, the lower arm still touching the hip. “To Turn to the Left.” Carry your hand tothe left, and bend it back slightly from the wrist, thumb pointing to the front (lower arm touching the hip). “To Pull Up.” Keep the hand low, the body back, and shorten the reins by drawing back the bridle arm (lower arm touching the hip).* * Again, adjust one’s arm position and length of the reins to accommodate the Forward Seat or for with whatever seat one rides. In breaking in horses, teach them by the use of the inward rein to turn their heads into the new direction; at the same time always make them feel the pressure of the outward rein against the neck. Thus when the rider(with the reins in his left hand) carries his hand to the right, the right rein being there first felt, inclines the horse’s head that way, and the pressure of the left rein against his neck, which unavoidably follows, induces the horse to turn to the right. To the left, vice versa. These aids are so simple and so marked, that the man can never make a mistake, nor can the horse misunderstand them; hand and body work together; they are sure to be resorted to on an emergency, because natural to the man, and therefore the best to adopt in practice.

Copyright ©2012, Dan Gilmore, all rights reserved |

|